Back to Getting Started

Philosophy, Practise and Practicalities

Gesture

In my opinion, the organising principle or priority of classical figure drawing is the capturing and transmission of gesture, either from observation or imagination. By gesture I mean both the emotional state of the model and their implied intention. We are reading their psychological and physical state and what they mean to do in their next breath. Are they awake or asleep, anxious or confident, relaxed or engaged? And to what degree? What will they do next? Are they in motion or still? Where will their body be in another second? What would it feel like to be them? What are they doing? This is the story we are implicitly telling. (To extend the story, we can add context - an exhausted figure chained to an oar is a different story to an exhausted figure with a pack and smiling companions in the Swiss Alps. But the story implied by the figure itself is primary, and can support the surrounding narrative, and so is our primary concern in this course).

Natural form/ Anatomy

Layered onto this central idea is the beauty of human anatomy (or animal anatomy in that case), the eternally fascinating way that nature organises its parts into structured fluidity. Some muscles are contracted while others are relaxed, some compressed while others are stretched, and meanwhile the spatial organisation of certain structures, for instance the critical symmetry of the pelvis or ribcage is retained beneath.

The transmission through drawing

Finally there is the magic of the craft of drawing itself - the use of marks on a flat surface to imply space, anatomy and light, as well as the state of mind of the artist. When done well we marvel at the economy of mark or the refinement of rendering that transmit these elements powerfully, and give us the joy of witnessing the mastery and inspiration of the artist. We are with them in their fascination, empathy, joy and struggle.

Classical?

The term classical may seem anachronistic, and you might associate it with a kind of stuffy neo-classicism. But the way I am using the term is to refer to the idea of seeking a balance between the elements described above. None should take precedence to the extent that another is destroyed. The balance may change, but the care for all the aspects is central. This care for all elements, I believe, is inspiring to us at least partly because it is equivalent to balancing the aspects of one's life - in each moment we make choices about what to do to fill our days, and wisdom seems to be at least in part about restraining excess in one area that is too detrimental to other aspects. The pursuit of harmony within complexity is a central aspect of life, and the reason that I find intentionally ugly or slapdash work within the modern or post modern traditions unfulfilling - it may communicate an idea, but only in the form of a cheap illustration. The craft of a work is not merely superficial - the effort and care to make a thing as beautiful as possible, even if the subject matter is confronting or dark, has its own deep meaning.

Drawing as “relational notation”

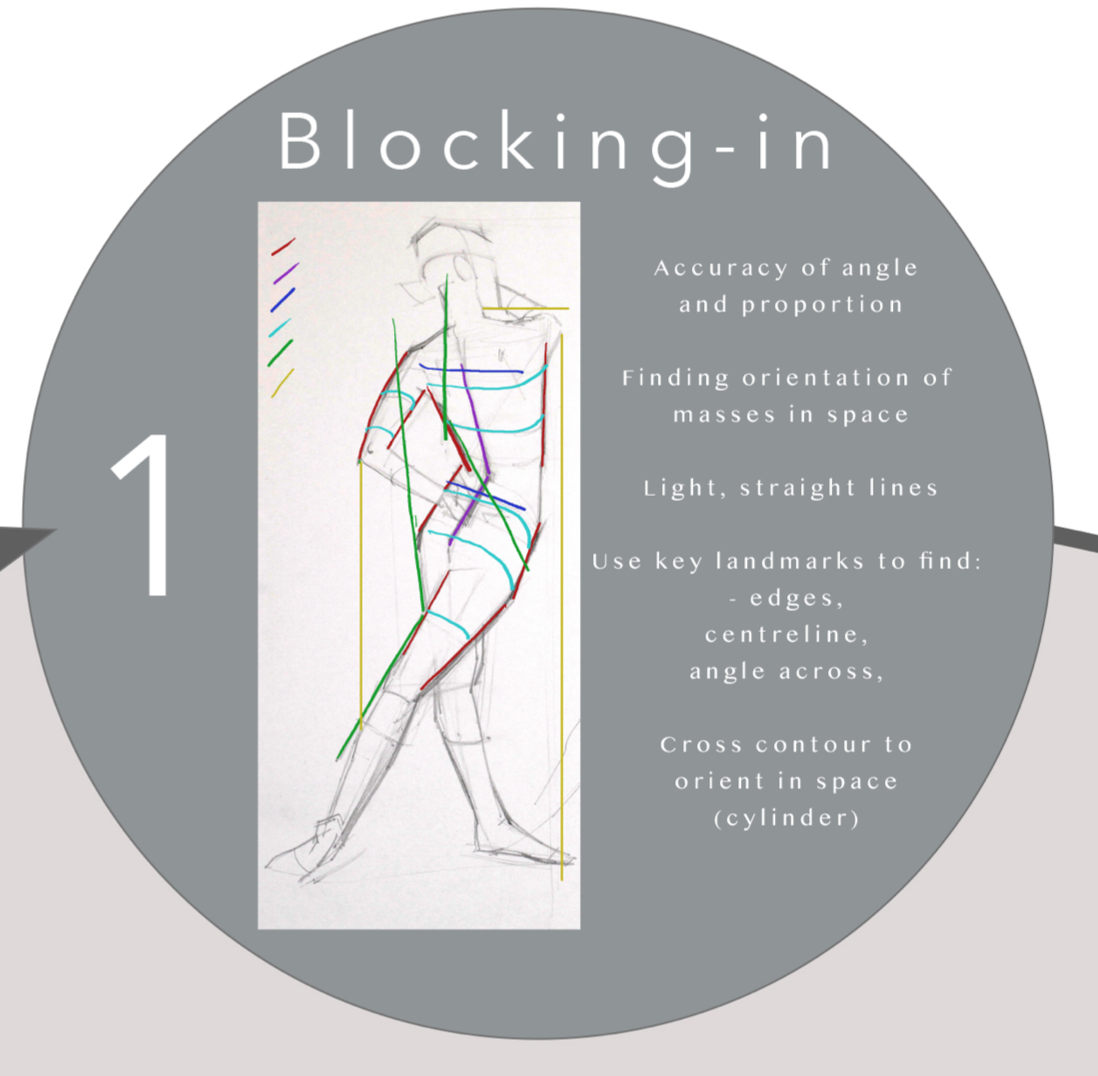

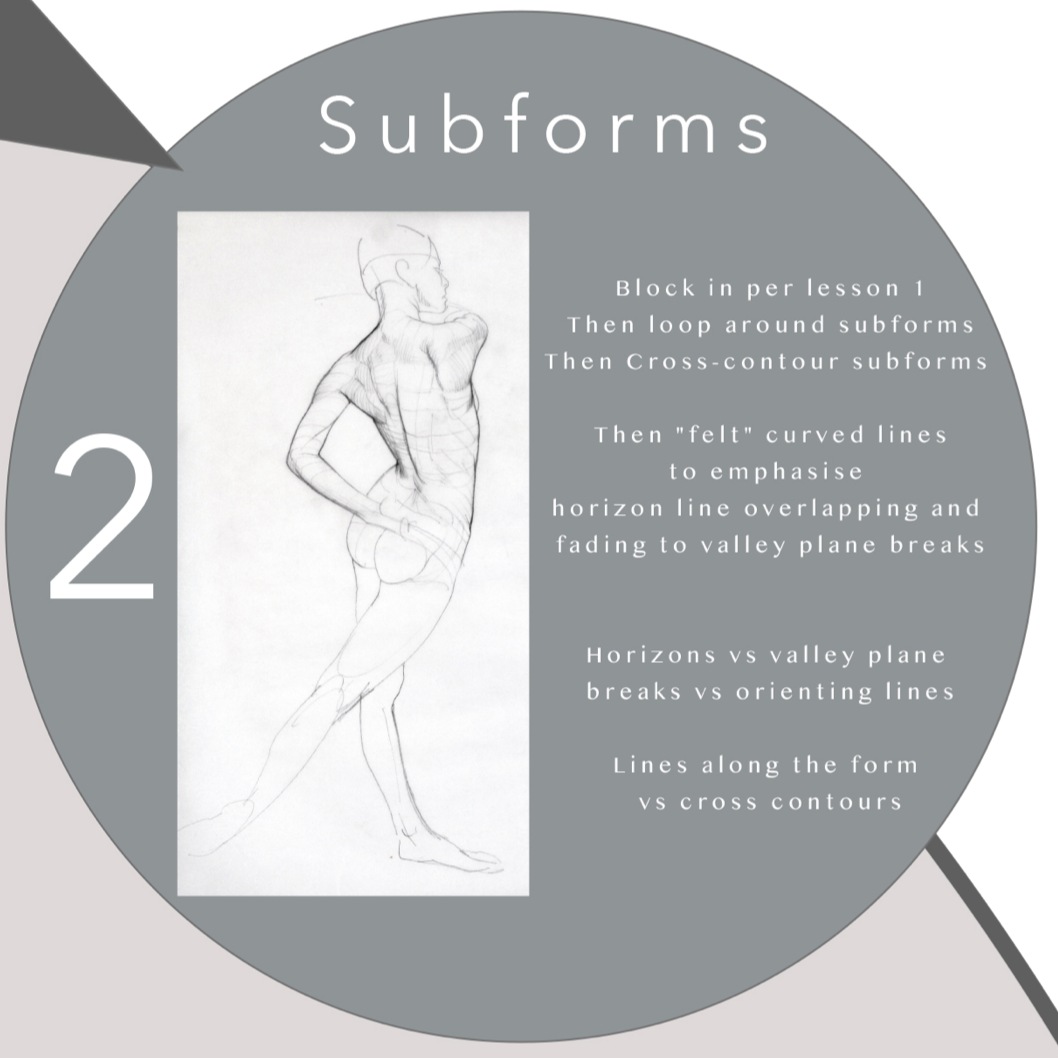

Drawing is not a matter of look and put, but rather of look, understand and translate. It is a notation of hierarchical relations - which is to say that there are primary and broad relations that should precede and organise smaller relations. These broad relations might be purely spatial and might utilise a simple straight mark to notate the apparent angle between points or they could be broad sweeping curves that capture design or gesture in the arrangement of parts of the body. They can delineate and sculpt the horizon of a form as it turns away, or notate the position of plane change across a form. They can imply the separation of light and shadow as light falls on form, or wrap around the form as a cross contour or piece of rendering.

The need for technical and practical training

So, we are drawn to the sublime beauty of natural form, to the human figure and face as expressions of state and being, to story telling about what the person is doing and feeling, and our own feelings about what it is like to be in the world. These are large, emotional, intuitive things. As humans, a social species, we are hardwired to find the the human form extremely salient, which is to say we are pulled towards it as important. These are the high level things, the goals to capture and transmit.

And yet we require the intellect, and disciplined training to develop skills and knowledge to the point where they happen more automatically and we can actually address the big things we are most interested in. So, like a classical musician practising scales, learning the structure of musical tone and rhythm, and cultivating physical efficiency in playing the instrument, we must attend to the unromantic practicalities of our craft.

In drawing we discipline the eye to develop habits in what we look at and annotate, and the process of building form, building anatomy. We study the structure of the body and how it changes with pose and movement, we study both the general, ideal human form as well as how this varies with the unique character of the model. We get the feel for form, gesture and anatomy, and how these elements are mutually dependent. We take the figure apart and then, most importantly we put it back together. And ultimately we aim to get so intuitive with fundamentals that we just follow our intuitions with the pose. Like the concert pianist playing Rachmaninoff, eyes closed, who does not think about the notes but rather the psychological shape that those notes form.

And so the logical and the emotional begin to merge, the former supporting, focussing and articulating the intuitions of the latter.

Practical Considerations

We will be holding the pencil in a mostly overhand grip because this tends towards better control over time, a broader awareness and vision, and can be transferred between the pencil and short media such as pastel or charcoal. This might take some getting used to, but it is time well spent, as it tends to give a better result than a writing grip over time.

We will be using a range of types of mark to notate and represent a variety of elements within the figure - straight lines, arcs, weighted contours or cross contour, and calligraphic mark. Each has their own flavour and feel, and can be used to in different combinations to annotate relationships, depict edge contours, or imply the surface of the form.

Standing at the easel, either upright or desk easel? Sitting at a desk/ donkey? Primarily I want you to be comfortable so you can concentrate on the topic of the class, and learning can happen most easily. There are plenty of each option in the studio. Over time, you might like to try each one as each has its pros and cons. As with the overhand grip, each way takes some getting used to physically, but if you give it some time, it will offer its particular advantage.

I will be going through a range of drawing media which can be quite suited to particular drills we will be doing - you are welcome to try all of them during the course, or stick to pencil if you prefer.

The role of the model:

An Artist's Model provides the raw material for both learning about the figure and directly as a source of material for making a powerful drawing, through both the physical appearance and gestural content of poses. While the human body, as part of nature, always has its beauty and sublime organisation, as well as gestural content, a really good life model can help the artist immeasurably by amplifying gesture, just as a dancer or actor transport us with their ability to stylise and emphasise. Physical type is also a factor in what makes an exceptional artist’s model, but this is not merely a matter of body fat percentages, gender or age. Rather, a model who is good to draw is one whose underlying structure is helpfully clear, who can be "read" well, from whom the artist can more readily transcribe the relations from which the gesture is composed. Finally, but not least, is a model who cares about the work the artist is doing and wishes to contribute to that with their energy and effort can psychologically support and encourage the artist.

While it is possible with enough study to learn to draw the figure in a fairly convincing way from imagination, there are certain proportional relationships that are unique to an individual model that are hard to define and replicate. For this reason most figurative artists seek out a model for their work. At the most obvious level, a person's arm length is often related to their leg length, and their degree of muscular development and definition in one region will be related to others. But there are patterns that exist between parts of the body, and the very way that they person holds themselves and moves that are extremely subtle and hard to put into words - part of the reason that we draw from the model!

The traditional method of learning to draw is to work from the plaster cast of anatomical and idealised sculpture (which is to say generalised or with character subtracted) leading to drawing from the unique human model from life. In this way we sensitise ourselves to both the general as well as the unique character of the model in front of us - both are necessary. Today this practise is not as common and people often want to launch into drawing from life, which means that we need to make a specific effort to attend to understanding and learning to work with the generalised or idealised figure from imagination separately. This helps us to better appreciate the individual character of the model in front of us, in how they vary from the generalised, and to draw from this context to better make the drawing comprehensible by knowing what to emphasise or deemphasise.

What I want for you:

Drawing is a challenging thing, particularly drawing the figure. But with the right approach it can be an enjoyable flow state experience. To do that, we need to work in the channel between too challenging (stress) and too easy (boredom). The drills that I am offering can be considered as games, with a set of rules to play. As your skills and speed improve, the game will change with you, with more factors being added in.

I would like you to consider that perhaps drawing is not a thing you learn then just leave behind. To be sure, I believe it will support you in many other aspects of your artistic efforts and indeed in general for your ability think and see well. So if you do this one course and move on that will be time well spent.

However, I see life drawing as a practise in the sense that a martial art, meditation or yoga is a practise. It is an ongoing discipline and a way to engage with the most astonishing and intimate subject of all - the human form. It is as familiar as it is bewildering when you make an attempt at representation. Each of us is living our own universe, our subjective experience unique but related to the universal human experience. And the body is the outward manifestation of that the - the skin we see is the skin of an interior world, the skin of that which it is like to be the other.

Drawing from the model is something that I do several times a week, a practise that keeps me humble and brings me back to the essentials of what matters, to the evocation of the interior world hidden in the concrete details of the superficial.

In Closing

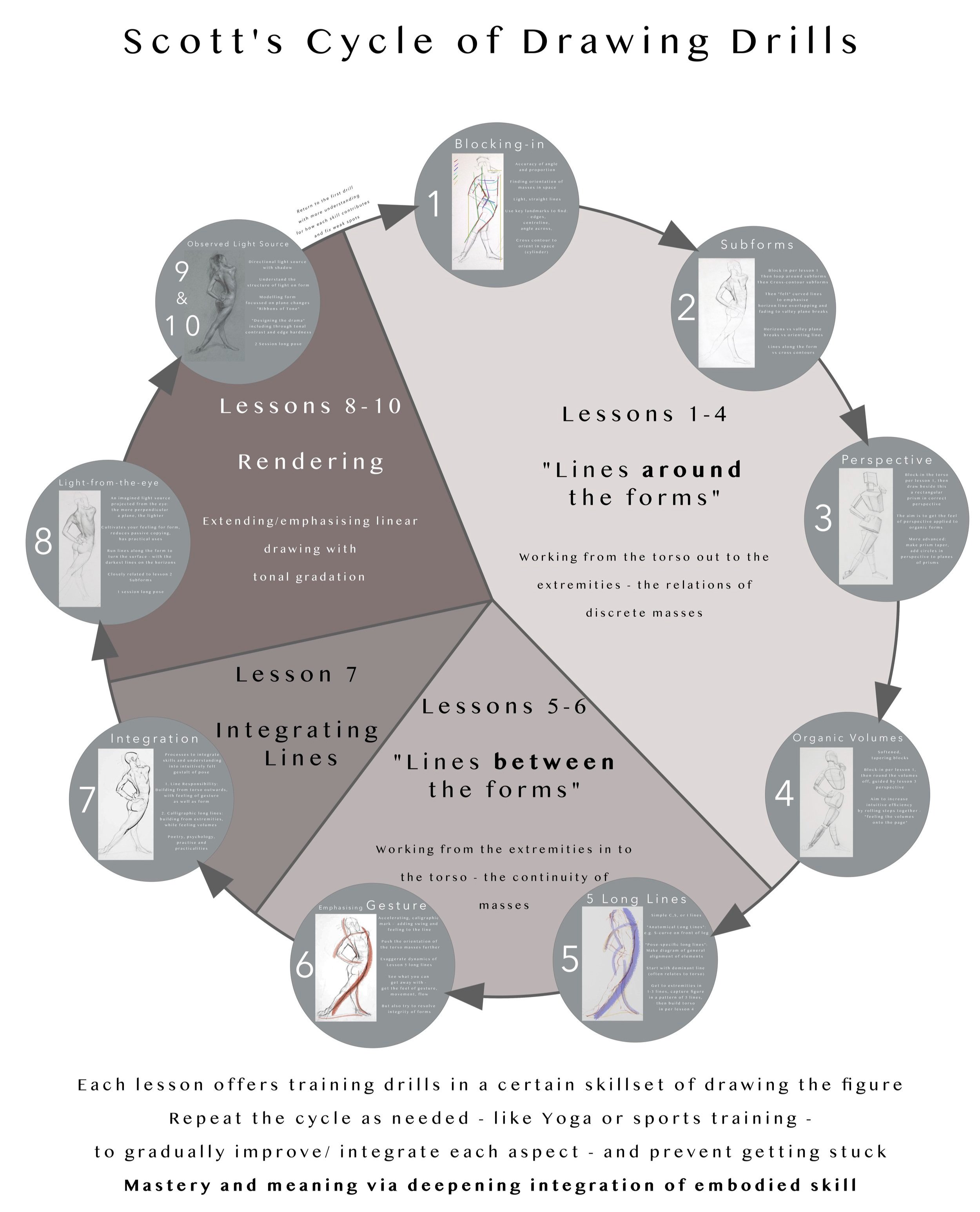

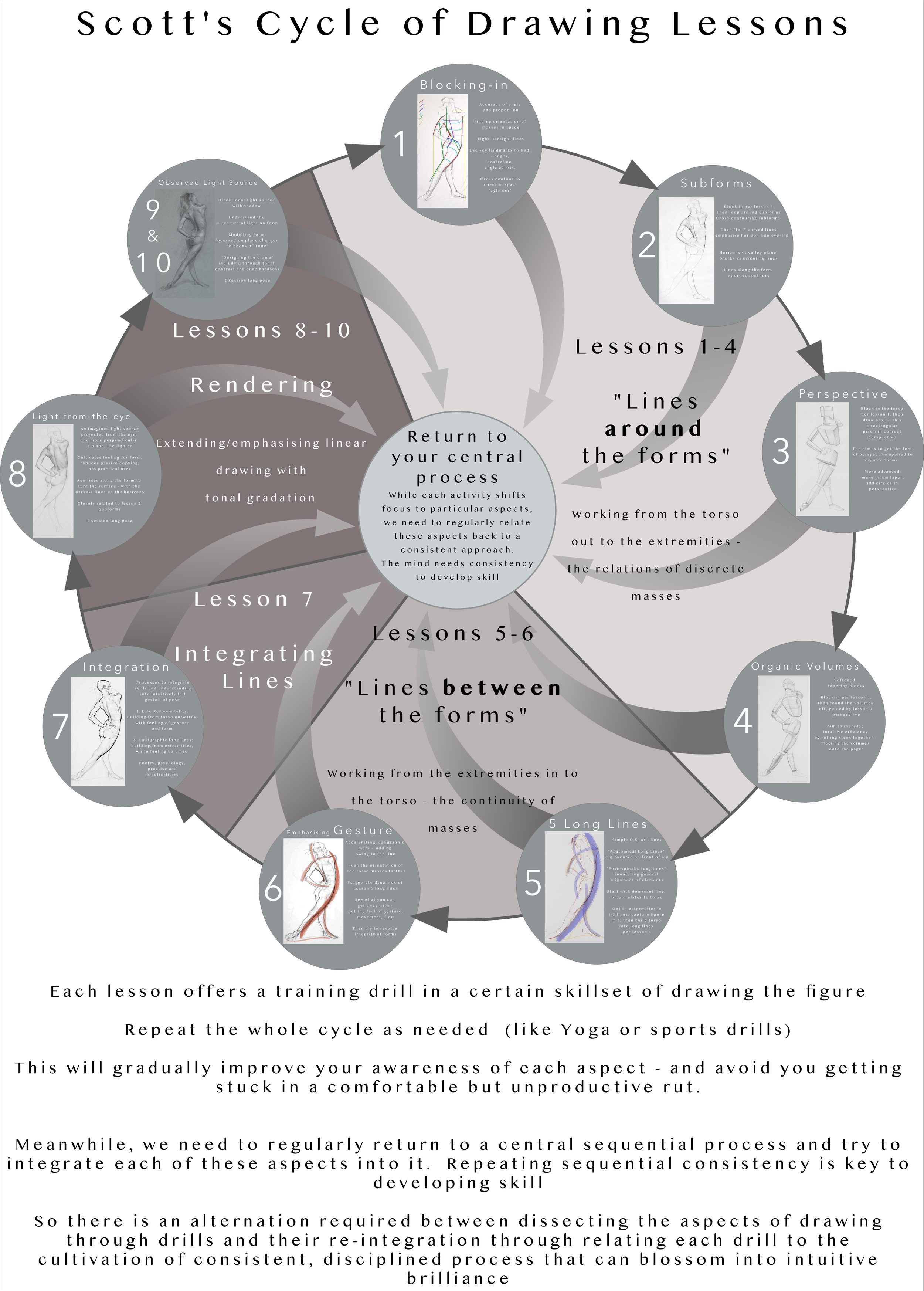

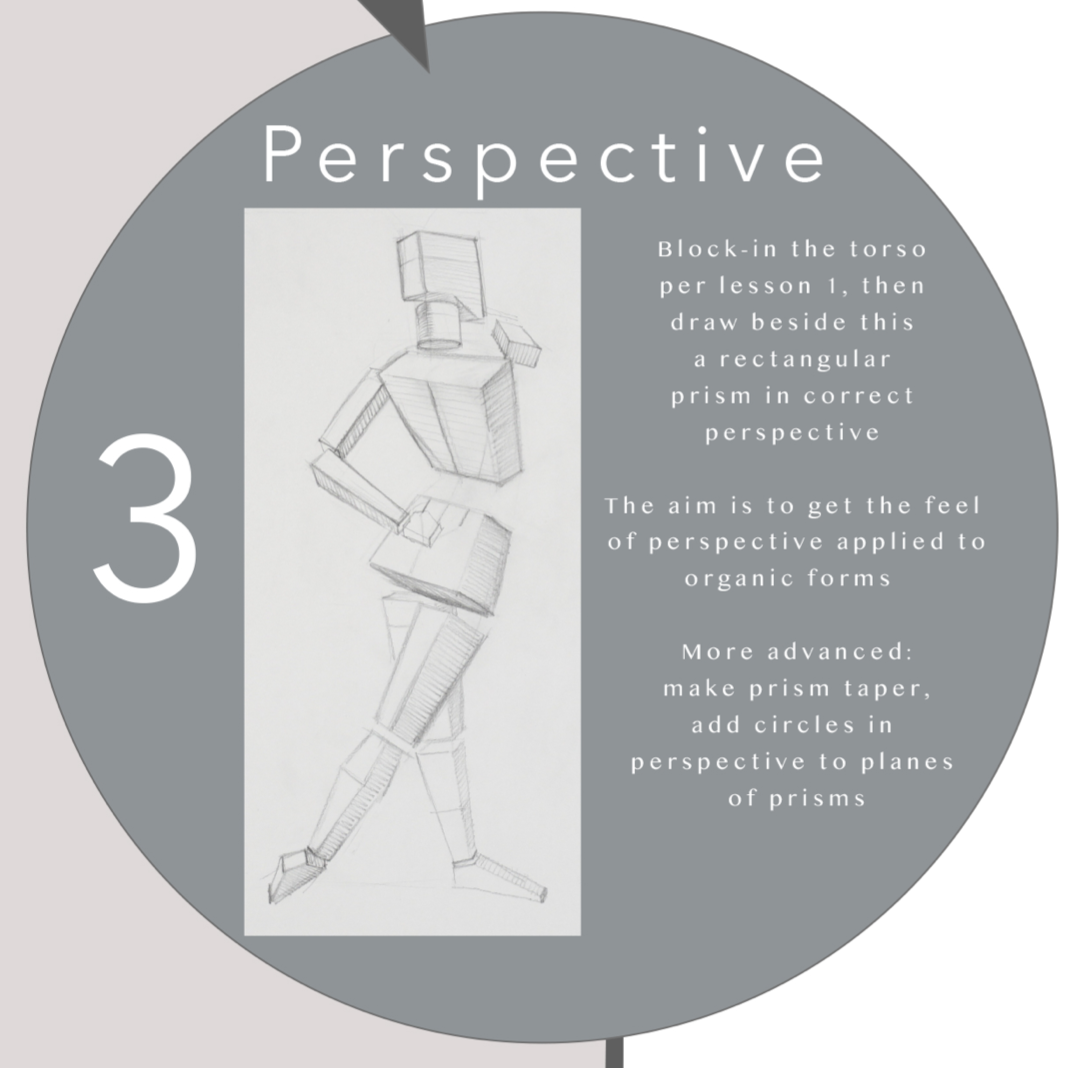

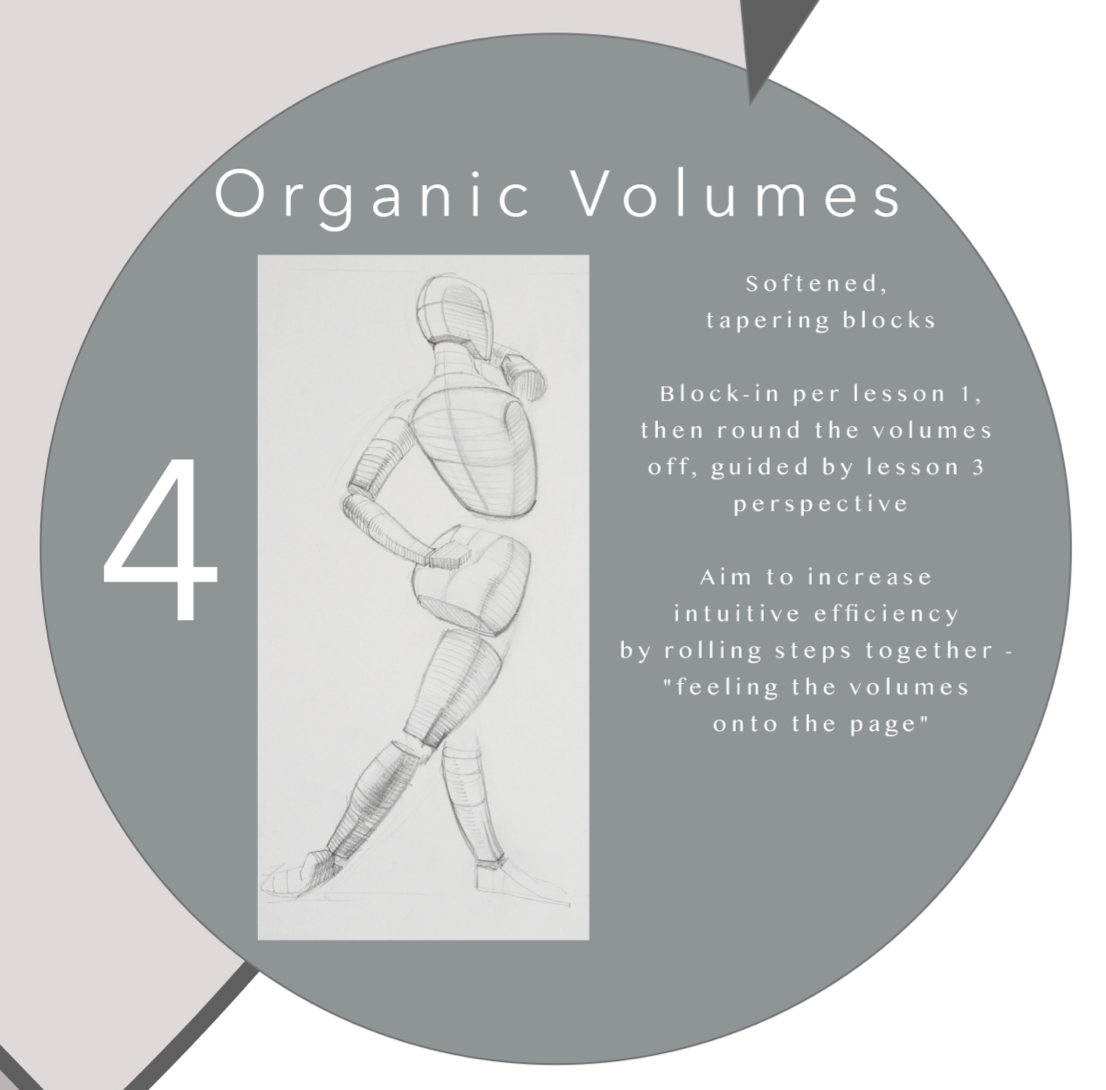

The spiral theory of knowledge - cycling through the drills

The activities in this course are intended to be revisited multiple times, with each visit informed by the previous cycle. This is because the skills and understandings of each activity are partially dependent on each the others. Try to strengthen the aspects you are weakest at and see this benefit all the other approaches. At each stage the power and quality of your perception and skill will gradually deepen.

Avoiding the Rut

By following the drills, for at least part of your weekly drawing practise, you can prevent yourself falling into ruts where you draw the same way each time and don’t make much progress. I have seen this many times with people I see at drawing sessions and also at times in my own progress - it is easy to get stuck in a comfort zone of the parts you usually focus on. Or trying to break out of a rut by changing media (eg trying charcoal or pastel when you are used to pencil) but alas this leading to little progress because your focus and habitual techniques remain the same.

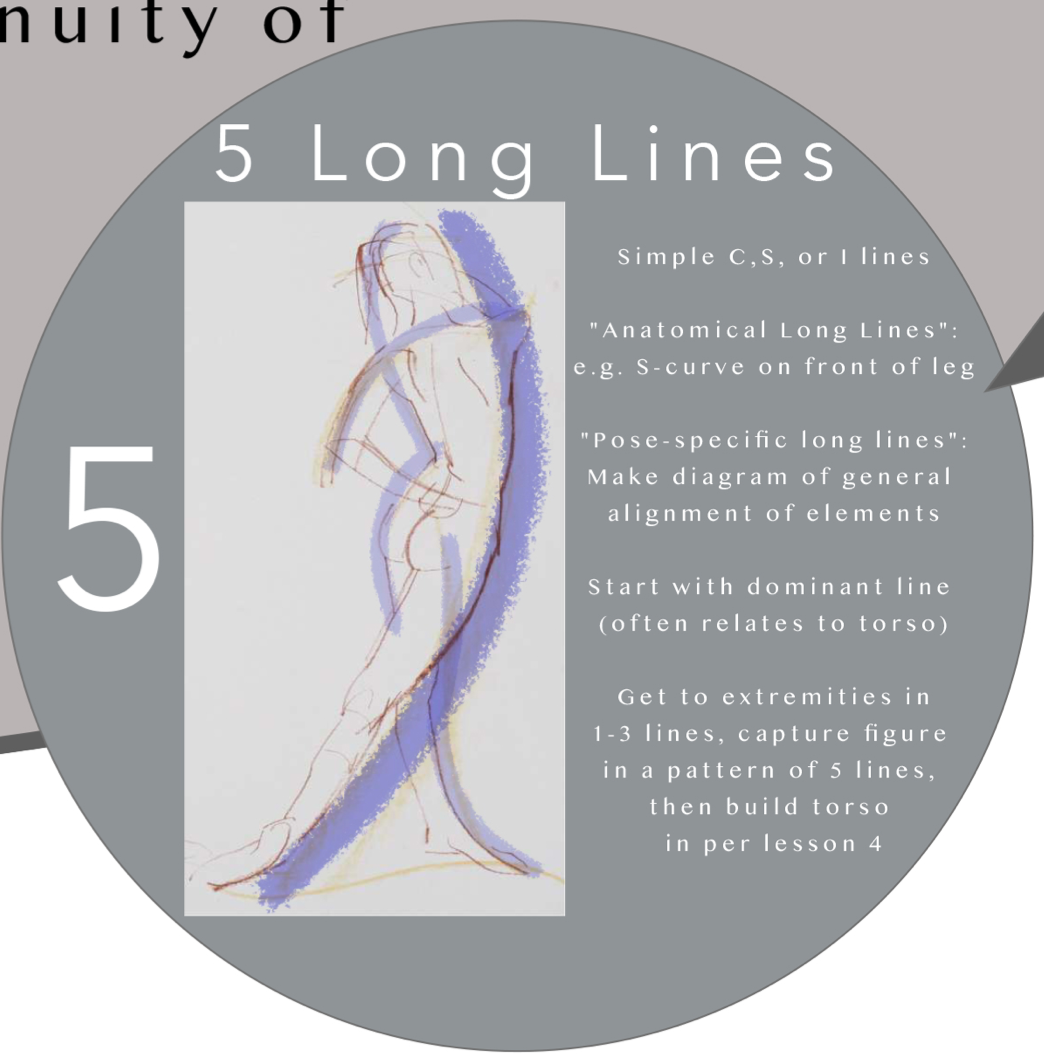

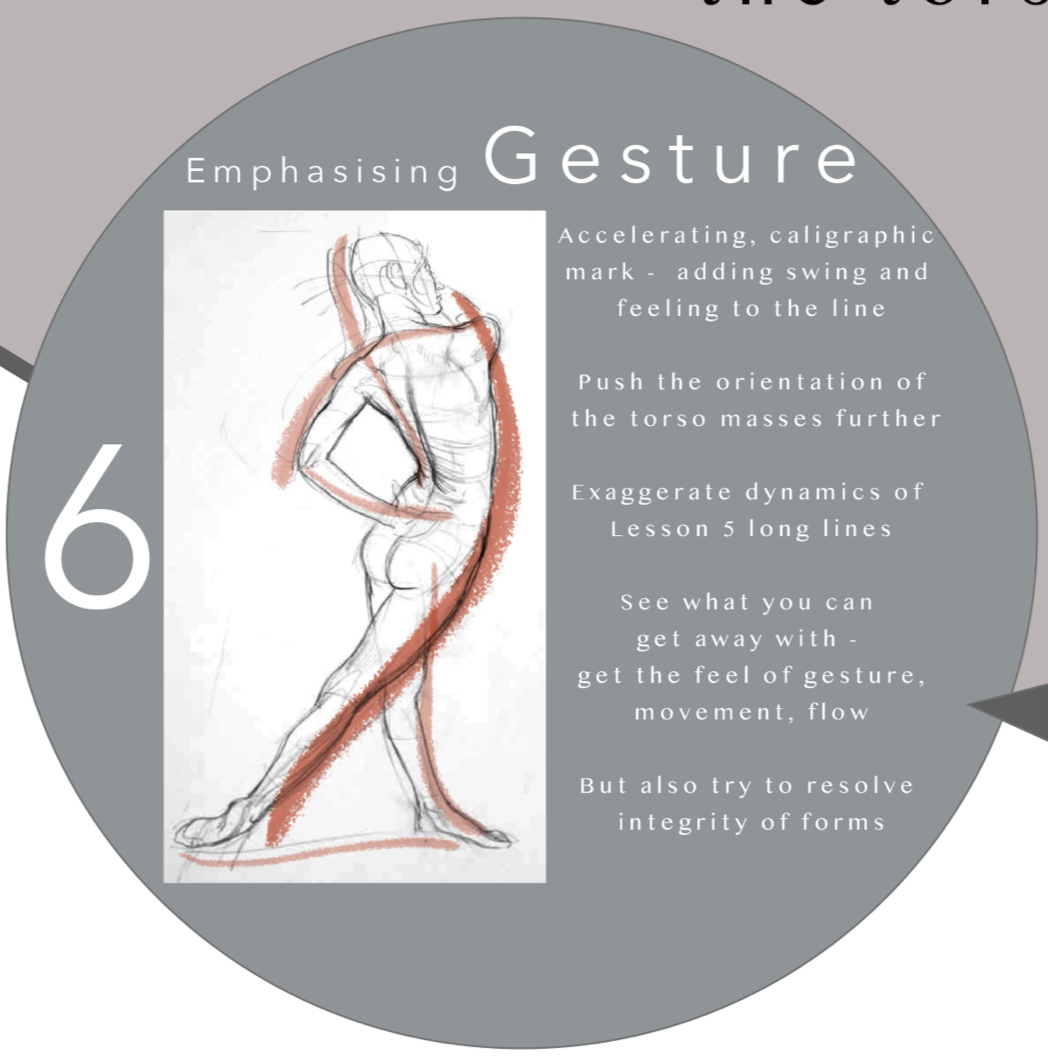

Building a central approach

It might seem paradoxical, but while I strongly believe in intentionally cycling through different drills as described above, there also should be effort put into cultivating a central process of drawing that gradually integrates the various skills honed in the different drills. Consider the description of lessons 8 through to 10 which involve developing a more rendered drawing during a longer pose as such a process. The process here involves using the “long lines” to establish the pattern of the figure and scale it on the page, then finding the torso masses within this setup, and then clarifying the contours (of at least part of the figure) within this context, prior to beginning to render (model the figure in light and shade).

By repeating that central process we become fluent with the steps involved and intuitive leaps begin to happen. Yet, if we can also sometimes return to the drills, we can develop the weak areas that this process relies upon.

Separate and integrate, divide and conquer, until finally you are not thinking or dissecting at all, but only exploring and celebrating what you love.